Corporate Executive Power Explained – CEOs First, Shareholders Last

Once upon a time, corporations were supposed to be simple. Shareholders put up the money, boards kept watch, and executives were hired hands. The CEO’s job? Run the company for the owners.

That’s the fairy tale.

The reality: executives have turned themselves into the owners, boards into lapdogs, and shareholders into background noise. Corporate executive power is no longer about stewardship. It’s about self-enrichment — with a system built to protect those at the top.

Table of contents

The Myth of Shareholder Control

On paper, shareholders run corporations. In practice, they’re irrelevant.

Why? Because most “owners” don’t act like owners. Shares are held by passive funds, pension schemes, and index trackers. Millions of investors scattered around the world, none with the time or will to show up.

That silence gives executives a free pass. As long as the quarterly numbers look decent and dividends trickle in, they can do whatever they like.

Think of it like being a landlord who never visits the property. The tenants can run a nightclub out of the basement, and you’ll never notice.

Boards as Lapdogs

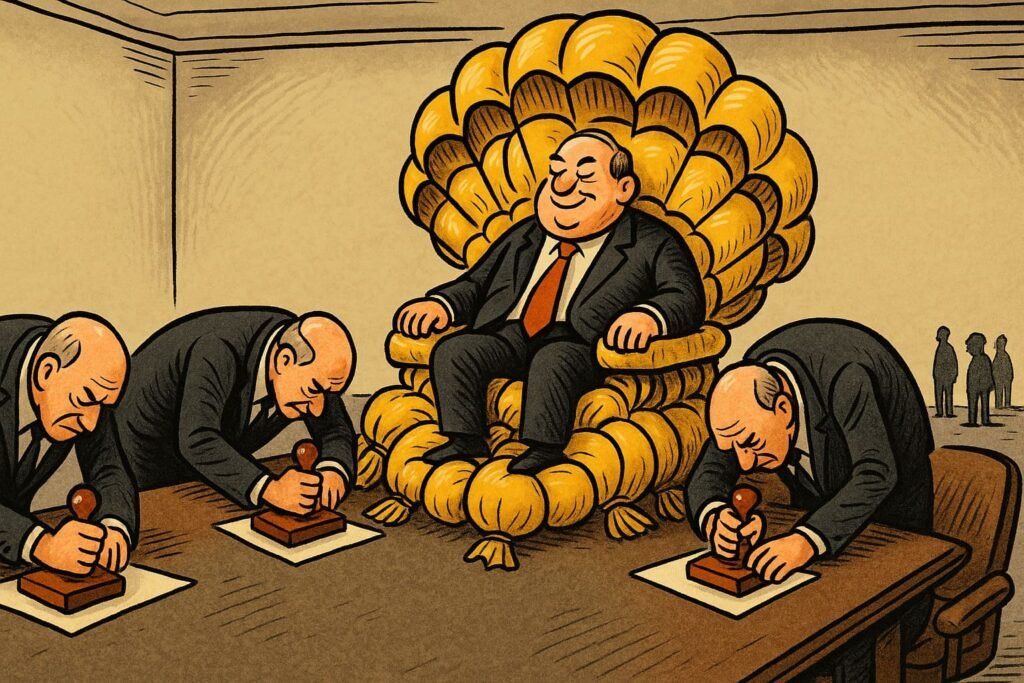

Boards of directors are supposed to protect shareholders. Instead, they protect executives.

How?

- CEO-approved directors: executives often recommend who joins the board. Surprise, they pick loyalists.

- Career directors: many sit on five or six boards at once. Their job isn’t oversight — it’s networking.

- Closed clubs: the same faces rotate between companies, cashing fees while rubber-stamping whatever the CEO wants.

A watchdog that eats from the master’s hand isn’t a watchdog. It’s a pet.

The Looting Toolkit

Executives don’t just get rich. They’ve perfected a system of looting dressed up as “incentives”:

- Short-term bonuses – Targets engineered through accounting tricks like share buybacks or cutting staff. Long-term health ignored.

- Golden parachutes – Fail spectacularly? Walk away with €20 million. Accountability without consequences.

- Stock options – Inflate the share price, cash out, and leave the wreckage for the next boss.

It’s not stewardship. It’s a smash-and-grab job, repeated every quarter.

The HR & DEI Smokescreen

Ever wonder why HR departments and DEI programs mushroom in corporations? They’re not just about “equity” or “inclusion.” They’re shields.

- HR builds endless rules and codes that protect management from legal or cultural criticism.

- DEI training creates a climate where questioning leadership decisions can be labelled “unsafe” or even “bigoted.”

The message is clear: complain about your boss, and you’re not just insubordinate — you’re a problem for “inclusion.”

Morality as a firewall.

Too Big to Question

The bigger the corporation, the safer the executive.

When an organisation has 200,000 employees across 50 countries, who can really understand what the CEO is doing? Complexity becomes camouflage. Layers of middle managers act as buffers. Bureaucracy turns the executive suite into a fortress.

By the time shareholders, journalists, or regulators try to follow the trail, the bonus has already been paid, the parachute packed, and the CEO has moved on.

Breaking the Illusion of Control

Corporate executive power thrives because everyone pretends the system works:

- Shareholders pretend their votes matter.

- Boards pretend to be independent.

- Politicians pretend to regulate.

In reality, the system is rigged for insiders. The only way to rebalance power may be the nuclear option: break up corporations that are too big to govern. Smaller firms mean fewer shadows to hide in, fewer layers to abuse, and fewer excuses for executives to loot unchecked.

Conclusion

Corporate executives were supposed to serve shareholders. Instead, they serve themselves.

Boards nod along, HR builds walls, and shareholders snooze in the background while the C-suite grows rich.

It’s not corporate governance. It’s corporate capture.

👉 For the bigger picture of how managers — not just executives — now run the world, see [Managerial Capitalism Explained].

Related Links

- Managerial Capitalism Explained – The Great Swindle We All Pay For

- Stakeholder Capitalism – The Corporate Takeover of Democracy

- DEI – Inclusion for Sale

- For the bigger picture of how corporations gained their power, visit The Power of Business & Corporations Explainer Hub.

FAQ

What is corporate executive power?

It’s the outsized influence CEOs and top managers hold over corporations, often prioritising their own rewards over shareholder or worker interests.

Why don’t shareholders control corporations?

Because most shares are held passively through funds and pensions. Owners rarely act, leaving executives free to dominate.

What role do boards play?

Boards are supposed to oversee management, but often act as rubber stamps. Executives frequently choose who sits on them.

How do executives enrich themselves?

Through short-term bonuses, golden parachutes, and stock options designed to inflate share prices temporarily.

Why is executive power dangerous?

Because it concentrates wealth and decision-making in a small circle, undermining accountability, shareholder rights, and even democracy.