Transablism Explained – Disability as an Identity Costume

From Disorder to Identity Politics

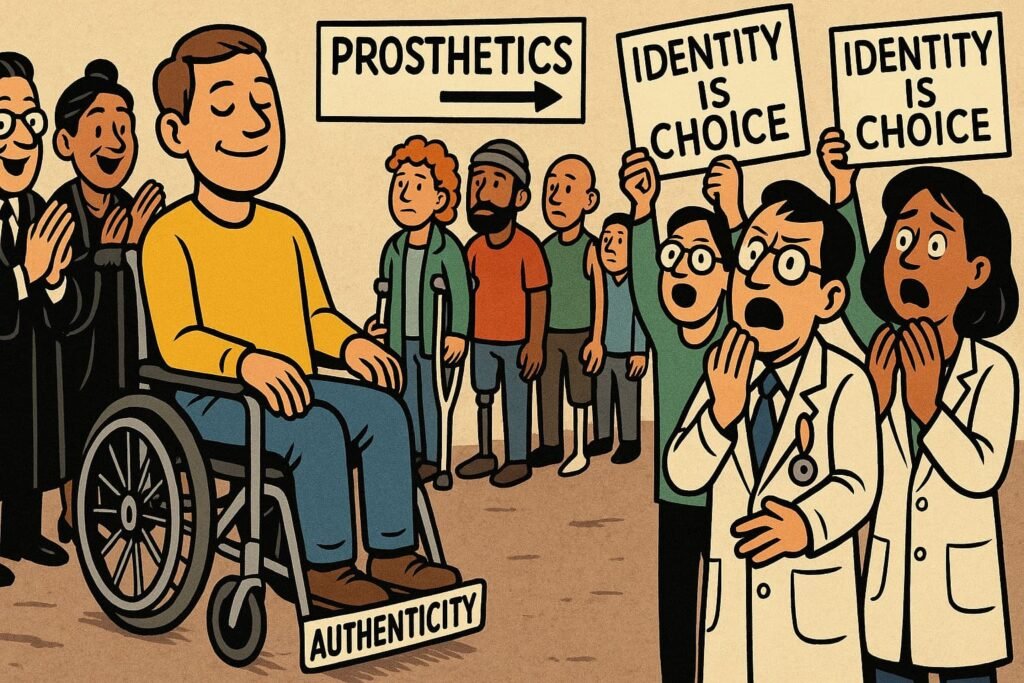

Imagine being healthy but desperate to cut off a limb, blind yourself, or otherwise disable your own body — not by accident, but as an act of “self-authenticity.” Welcome to Transablism: the belief that your “true self” is disabled, and that you need to make it real.

It sounds like satire, but it’s a genuine phenomenon. And in an age obsessed with identity, it’s being reframed as just another expression of the self.

Table of contents

What Is Transablism?

- Rooted in Body Integrity Identity Disorder (BIID): people feel their healthy body doesn’t match their internal identity.

- Some crave amputation, paralysis, or blindness to feel “complete.”

- It’s framed as identity expression, not pathology — turning disability into self-chosen authenticity.

In short: people sabotage their own health to feel like their “real self.”

Buzzwords of Transablism

Like all identity spin-offs, it comes with its own jargon:

- Transabled – An able-bodied person who identifies as disabled.

- Body Integrity Identity Disorder – The clinical label used as cover.

- Authenticity – The holy word: harming your body is “being true to yourself.”

- Appropriation – What critics call it: borrowing real disability for identity games.

- Lived Experience – Once again, personal feelings trump biology or common sense.

How It Shows Up in Practice

- Medical system strain: Some demand surgeries or prosthetics meant for the genuinely disabled.

- Online communities: Forums and blogs that glorify self-harm as self-discovery.

- Activist creep: A push to fold transablism into wider identity politics debates.

What starts as a mental health issue is reframed as a justice claim.

Why It Gains Attention

- Academics: New territory for identity theory papers.

- Media: Click-worthy outrage bait.

- Activists: Another cause to link with gender, race, and disability struggles.

- Therapists: A way to expand mental health categories (and billable hours).

The Consequences of Transablism

- Appropriation: Disability turned into a costume for the able-bodied.

- Resource drain: Prosthetics and care systems strained by voluntary cases.

- Moral absurdity: Real suffering trivialised as self-expression.

- Slippery slope: If every identity claim must be validated, where does it stop?

Why It Matters

Transablism forces a question society is too polite to ask: is every identity valid, or do some cross the line into harmful absurdity?

By dressing up self-harm as authenticity, it undermines the struggles of people born with disabilities — people already short-changed by systems obsessed with slogans over services.

👉 For the broader academic roots of disability as politics, see our explainer on Disability Studies.

FAQ: Transablism

What is Transablism?

The belief that a healthy person is “meant” to be disabled, often leading to self-inflicted disability.

Is it the same as Disability Studies?

No. Disability Studies reframes disability as oppression politics. Transablism is an extreme offshoot where able-bodied people choose disability as identity.

Why is it controversial?

Because it trivialises real disability, wastes resources, and reframes self-harm as authenticity.

Is it a mental health disorder?

It’s linked to BIID, but activists try to frame it as identity instead of pathology.

What’s the danger?

That it normalises self-destruction as a lifestyle — and turns real disability into another identity game.

👉 For the academic roots of how disability was reframed as oppression politics, see our explainer on Disability Studies.